Fibers in PHP: A new opportunity for async PHP?

It looks like PHP will get fibers soon with PHP 8.1! That’s awesome! Or is it?

What are fibers?

I think the Ruby documentation does a good job at describing what fibers are:

Fibers are primitives for implementing light weight cooperative concurrency [in Ruby]. Basically they are a means of creating code blocks that can be paused and resumed, much like threads. The main difference is that they are never preempted and that the scheduling must be done by the programmer and not the VM.

Will fibers bring async to PHP?

No. Maybe yes? This is perhaps one of the most common misconceptions about the fibers RFC and also where things become tricky, so hear me out.

Fibers are a low-level construct to manage control flow. They allow you to build (synchronous) functions in such a way that they can be paused and resumed. It is up to the person developing this function to define where this function can be paused and what event it waits for to resume execution.

Fibers themselves do not schedule these executions, but they allow an additional scheduler to resume a paused fiber. In any realistic environment, this would be handled through an event loop implementing the reactor pattern. Now, the fiber API itself does not provide such an event loop (which I consider a good thing).

This means you would still have to use something like ReactPHP, Swoole or Amp to provide async execution models or to build anything that can actually execute concurrently. This means that with or without fibers, async PHP will be provided by external libraries.

However, at the same time fibers have the potential to bring async PHP to more projects. From an average developer’s perspective, they will never interface with fibers at all. Fibers can be used as an implementation detail in async libraries so that async functions look just like a synchronous API, but with the help of the event loop can execute something asynchronously internally. This means there’s a chance we will see more async implementations in the future because they integrate more seamlessly into synchronous environments.

Do we need fibers for async PHP?

No. As detailed in the previous section, we need a scheduler (or event loop) in order to run things asynchronously or concurrently.

This means you would still have to use something like ReactPHP, Swoole or Amp for async PHP. With or without fibers, async PHP will be provided by external libraries.

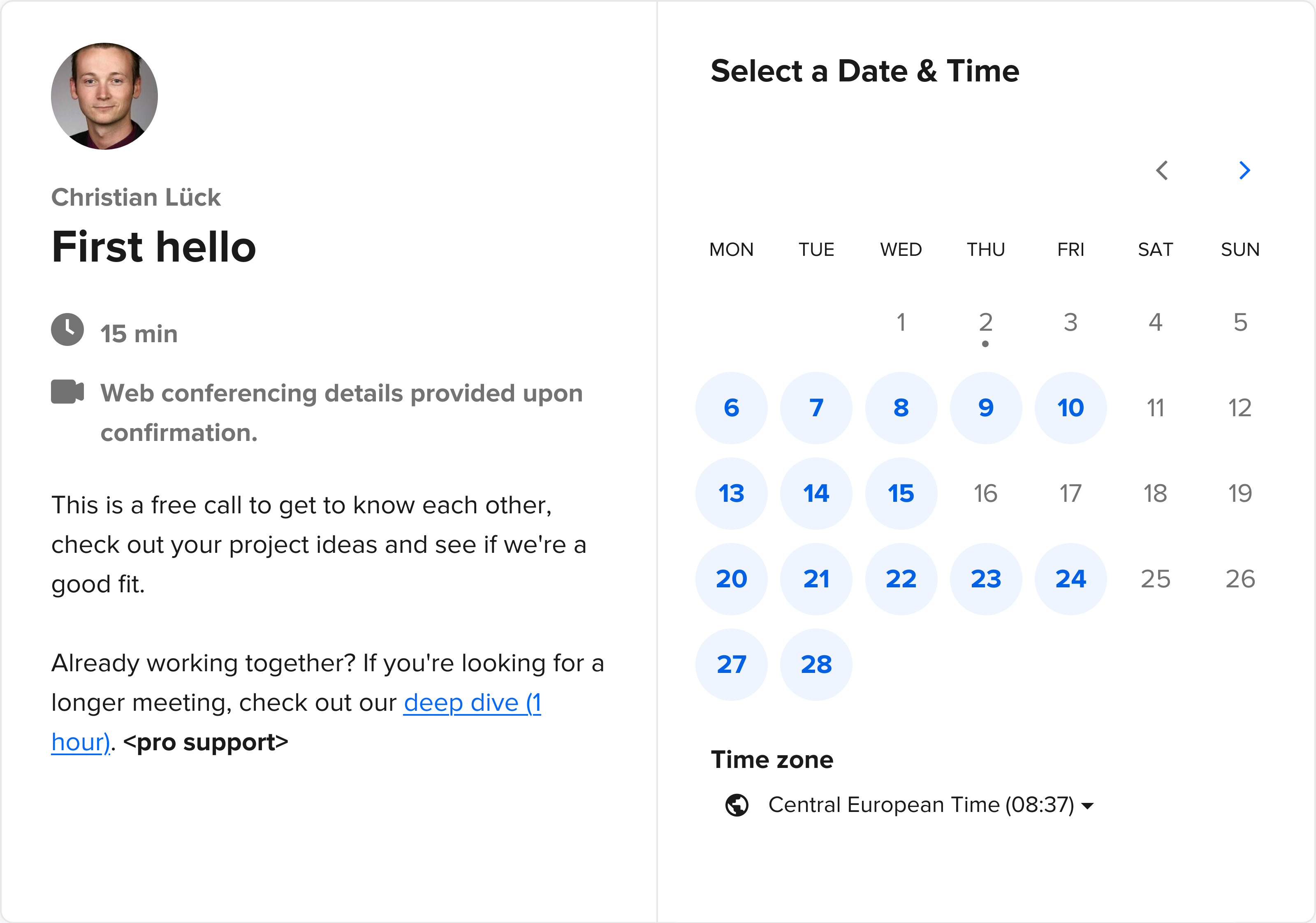

Full disclaimer here, I’m one of the maintainers of ReactPHP and we’ve built hundreds of production-grade projects using async PHP. And with tens of millions of downloads, ReactPHP has clearly stood the test of time and has allowed thousands of projects to take advantage of async PHP. Personally, I’ve been using ReactPHP for years (I’ve started using ReactPHP on PHP 5.3) with great success. In fact, we also use ReactPHP at the core of my software company business and we’ve helped numerous projects to get the most out of PHP by leveraging async PHP in production with great success.

Fibers are one possible building block for asynchronous applications among others. Unlike ReactPHP’s promises, Fibers haven’t stood the test of time yet in the PHP ecosystem. Yet, we see potential for the fiber proposal to change the async PHP landscape for·ever – and perhaps for the better.

What problem do fibers solve?

Fibers address the “What color is your function?” problem.

Yes, that’s a somewhat lengthy post, but you may want to read it to fully understand the concerns. In short, it means that many languages have a distinction between synchronous and asynchronous functions. Worse yet, when using any asynchronous function, it makes your entire call stack asynchronous as well.

To see this in practice, let’s take a look at some code to send an HTTP request.

Synchronous

In synchronous code, sending an HTTP request could look something like this:

function fetch(string $url): ResponseInterface { }

class UserRepository

{

private $base = 'http://example.com/user/';

public function checkUser(int $id): bool

{

$response = fetch($this->base . $id);

return $response->getStatusCode() === 200;

}

}

$ok = $userRepository->checkUser(42);

if ($ok) {

echo 'User exists!';

}

Promises

In order to represent the eventual return value of an asynchronous function call, many language environments use promises. Some languages provide a native promise implementation, in other languages, this is commonly implemented in userland. In PHP, this would be provided by ReactPHP or Guzzle. Here’s the same example using promises to send an HTTP request:

/** @return PromiseInterface<ResponseInterface> */

function fetch(string $url): PromiseInterface { }

class UserRepository

{

private $base = 'http://example.com/user/';

/** @return PromiseInterface<bool> */

public function checkUser(int $id): PromiseInterface

{

return fetch($this->base . $id)->then(function (ResponseInterface $response) {

return $response->getStatusCode() === 200;

});

}

}

$userRepository->checkUser(42)->then(function (bool $ok) {

if ($ok) {

echo 'User exists!';

}

});

Promise-based designs provide a powerful and sane interface to working with async responses.

At the same time, we realize that this example can look more complicated than its traditional, synchronous counterpart.

In particular, by using the async fetch() function, our entire checkUser() method also became asynchronous and needs to return a promise.

This in turn has a direct effect on how the main application uses this method.

Coroutines

This is where coroutines come into play. Some environments prefer implementing coroutines with the help of generators to make this same control flow look more like synchronous code. Among others, you can find this when combining ReactPHP with Recoil or using the current Amp version:

/** @return PromiseInterface<ResponseInterface> */

function fetch(string $url): PromiseInterface { }

class UserRepository

{

private $base = 'http://example.com/user/';

/** @return PromiseInterface<bool> */

public function checkUser(int $id): PromiseInterface

{

return async(function () use ($id) {

$response = yield fetch($this->base . $id);

return $response->getStatusCode() === 200;

});

}

}

$userRepository->checkUser(42)->then(function (bool $ok) {

if ($ok) {

echo 'User exists!';

}

});

Accessing the async return value now certainly looks much easier.

However, we can see that this now requires wrapping this in a generator function.

Additionally, we now need a generator-based coroutine implementation providing an async() function

that hooks into the yield statement and manages control flow for our promises.

This means this can be a nicer API for some aspects, but we’re still dealing with promises after all.

Fibers

Fortunately, fibers can come to a rescue here:

function fetch(string $url): ResponseInterface { }

class UserRepository

{

private $base = 'http://example.com/user/';

public function checkUser(int $id): bool

{

$response = fetch($this->base . $id);

return $response->getStatusCode() === 200;

}

}

$ok = $userRepository->checkUser(42);

if ($ok) {

echo 'User exists!';

}

This sure looks nice, right?

In fact, with fibers you will no longer see that a function call is asynchronous at all.

Fibers allow you to express a synchronous program flow, so you don’t have to deal with any async execution at all.

Interestingly, this also means the average PHP application developer will also never interface with the Fiber implementation at all.

I think this is a great plus.

Fibers provide a building block to build functions that can be used in a synchronous or in an asynchronous environment without changes. Their internal workings hide the fact that it might be executing other functions asynchronously with the help of an event loop. Fibers can be used in both synchronous and asynchronous environments without using adapters in-between. This means there will be a chance of us seeing more asynchronous implementations because they integrate more seamlessly into synchronous environments.

However, this is no fair comparison with promises. The above example looks entirely synchronous – because it IS synchronous. In order to make a fair comparison between fibers and promises, we actually have to take a look at an example that sends concurrent requests.

What does concurrency look like in real-world applications?

Again, let’s take our previous example and how instead of checking one external API, we check two external APIs.

Synchronous

Changing this in our synchronous example isn’t a lot of work:

function fetch(string $url): ResponseInterface { }

class UserRepository

{

private $base1 = 'http://example.com/user/';

private $base2 = 'http://api.example.org/user/';

public function checkUser(int $id): bool

{

$response1 = fetch($this->base1 . $id);

$response2 = fetch($this->base2 . $id);

return $response1->getStatusCode() === 200 && $response2->getStatusCode() === 200;

}

}

$ok = $userRepository->checkUser(42);

if ($ok) {

echo 'User exists!';

}

Now assuming that the first service always takes 1s and the second always takes 2s, executing this takes a total of 3s. It’s easy to see why: Every call happens one after another, so times add up.

Promises

Likewise, we can change your previous promise example to fetch from two APIs:

/** @return PromiseInterface<ResponseInterface> */

function fetch(string $url): PromiseInterface { }

class UserRepository

{

private $base1 = 'http://example.com/user/';

private $base2 = 'http://api.example.org/user/';

/** @return PromiseInterface<bool> */

public function checkUser(int $id): PromiseInterface

{

$promise1 = fetch($this->base1 . $id);

$promise2 = fetch($this->base2 . $id);

return all([$promise1, $promise2])->then(array $responses) {

return $responses[0]->getStatusCode() === 200 && $responses[1]->getStatusCode() === 200;

});

}

}

$userRepository->checkUser(42)->then(function (bool $ok) {

if ($ok) {

echo 'User exists!';

}

});

We can see that adding this second API call didn’t change much about the structure.

Promises will execute "in the background" by default and we can simply wait for both results by using an all() function.

Now again assuming that the first service always takes 1s and the second always takes 2s, executing this takes only a total of 2s. Internally, promises are resolved with the help of an async event loop. This happens concurrently, so we have to wait for the slowest one to complete. We can see why this would show an even more significant improvement with high concurrency.

Coroutines

Likewise, we can change our original coroutine example to fetch from two APIs:

/** @return PromiseInterface<ResponseInterface> */

function fetch(string $url): PromiseInterface { }

class UserRepository

{

private $base1 = 'http://example.com/user/';

private $base2 = 'http://api.example.org/user/';

/** @return PromiseInterface<bool> */

public function checkUser(int $id): PromiseInterface

{

return async(function () use ($id) {

$promise1 = fetch($this->base1 . $id);

$promise2 = fetch($this->base2 . $id);

$responses = yield all([$promise1, $promise2]);

return $responses[0]->getStatusCode() === 200 && $responses[1]->getStatusCode() === 200;

});

}

}

$userRepository->checkUser(42)->then(function (bool $ok) {

if ($ok) {

echo 'User exists!';

}

});

We can see that adding this second API call again didn’t change much about the structure,

but also that it’s starting to look a lot like the previous promise example using an all() function.

This isn’t really too surprising considering this coroutine implementation would build on top of promises.

This is also why from my experience, coroutine implementations don’t usually bring a lot of value to many real-world applications (YMMV).

Now again assuming that the first service always takes 1s and the second always takes 2s, executing this takes again only a total of 2s.

Fibers

Let’s take a look at what our previous fibers example looks like when changed to fetching from two APIs:

function fetch(string $url): ResponseInterface { }

class UserRepository

{

private $base1 = 'http://example.com/user/';

private $base2 = 'http://api.example.org/user/';

public function checkUser(int $id): bool

{

$promise1 = async(function () use ($id) {

return fetch($this->base1 . $id);

});

$promise2 = async(function () use ($id) {

return fetch($this->base2 . $id);

});

$responses = await(all([$promise1, $promise2]));

return $responses[0]->getStatusCode() === 200 && $responses[1]->getStatusCode() === 200;

}

}

$ok = $userRepository->checkUser(42);

if ($ok) {

echo 'User exists!';

}

Wait a moment? Aren’t fibers supposed to make asynchronous simple? Kind of, but that’s not really what fibers are about. Fibers specifically help to avoid the "What color is your function?" problem (see above).

Fibers aren’t magic!

Fibers themselves do not solve concurrent execution. Fibers allow expressing a (synchronous) control flow. The moment we want to express an asynchronous control flow, we still have to resort to promises.

In this example, we need to use two functions provided by our async library of choice.

The async() function turns a fiber-based function into a promise that will be executed "in the background".

And the await() function that instructs the event loop to execute until it can return to your synchronous flow.

This async() function sure looks like magic!

It looks like it could turn any synchronous function into an asynchronous one.

Unfortunately, however, this only works with functions that use fibers that instruct the event loop internally.

Problem is, you can no longer tell whether this function can be used in an asynchronous context at all. It might as well block your entire non-blocking application and you would have no way of knowing it in advance. Fibers eliminated the distinction between synchronous and asynchronous functions. What started as a good idea means that you’re now missing important information and your only chance is to check the documentation for each function that you want to execute asynchronously.

What does this mean for the future of promises?

Promises are not going anywhere. But perhaps we’re going to see them a lot less often.

With fibers, we can see how consumers of an API don’t need to use promise APIs for many common use cases. I believe this is a good thing because it can make many of the simpler use cases much less complicated.

Whenever you want to concurrently execute multiple functions, you will still need to use async primitives. This means promises will remain a viable option for async program flows, just like they are today. This is not something fibers will make obsolete.

What does this mean for the future of coroutines?

As seen above, generator-based coroutines can be useful at times.

Want to take a look at my crystal ball? Once fibers become mainstream, their usage will likely fade into insignificance.

What about async / await keywords?

Out of scope for the current fibers RFC.

In fact, the way many languages chose to provide native async and await keywords

would lead to the main "What color is your function?" problem that fibers aim to address (see above).

This means it’s becoming less likely we will see these keywords used that way in PHP.

The above examples use async() and await() functions that would be provided by your asynchronous library of choice.

Personally, I still see a lot of value in having these basic building blocks as part of the language itself.

This way, we could potentially enable broad interoperability between different async frameworks.

But at the same time, these implementations have a much larger scope and are also somewhat more opinionated.

The good news is we’re starting to see more collaboration between these implementations… (more on that in another post).

What does this mean for the future of ReactPHP?

We’ve discussed this in the ReactPHP team already and we’re looking forward to native fiber support in PHP!

We’ve already started working on a future version that takes advantage of fibers that will be released once fibers become available. This future version will take advantage of fibers to provide async APIs that can be used just like their synchronous counterparts.

At the same time, we deeply care about our existing user base. We’ve always been committed to providing a rock-solid foundation for other projects to build on top of and just ditching everything for the “new shiny” is an absolute no-go for us.

That’s why we’re focusing our efforts on providing a smooth upgrade path between the current version and the future version. We will make sure to make the switch as seamlessly as possible. On top of this, we realize that some form of coexistence between current ReactPHP-based projects and projects that build on top of a future version will be inevitable. We will make sure to provide ways to combine and mix and match wherever possible.

On top of this, we will continue our long-term support (LTS) promise (see what I did there?) and will continue supporting the current version for the foreseeable future. With the help of my software company business, we will also provide professional support to ensure a smooth upgrade path also for commercial projects.

Additionally, we’re currently also working on Framework X which was always designed to bridge the gap between traditional, synchronous PHP and the shiny world of asynchronous PHP. With the integration of fibers into PHP, we’re excited this will become better than ever!

Should PHP have fibers?

I think fibers are a really interesting concept! We should absolutely have fibers in PHP.

But fibers don’t do what most people seem to think they do.

I’m the first to admit fibers sound great and it’s very hard to describe the nuanced details. Fibers seem to promise we’ll see native async PHP, but that’s really not what fibers are about.

Fibers do a great job at solving the "What color is your function?" problem. This means there’s a chance we will see more async implementations in the future because they integrate more seamlessly into synchronous environments.

Personally, I feel that some valid concerns have been brought up against the fibers RFC. I understand the RFC process and PHP internals can be harsh at times and agree that ideally, more discussions should have taken place before the RFC vote began. Some people suggested this entire feature should be marked as experimental only, so the question becomes: How much would we want to depend on something that’s an experimental feature only?

Let’s take this opportunity to have this discussion now. I think we, as the PHP community, should better get this right.